Just getting to the end of the day and surviving the night must feel like a miracle in the Gaza Strip. Palestinians “plead for safety”, wrote Philippe Lazzarini, head of UNRWA, the main UN relief agency in Gaza, in an “endless, deepening tragedy… hell on earth”.

It must be just as hellish for the hostages taken by Hamas and for the families of their victims. War is a cruel furnace that puts humans through terrible agonies. But its heat can produce changes that seemed impossible.

It happened in western Europe after World War Two. Old enemies who had killed each other for centuries chose peace. Will the war in Gaza shock Israelis and Palestinians into ending their century of conflict over the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan river?

The widow of Muhammad Abu Shaar

I’ve been watching a video of a woman wracked by grief, sitting next to the body of her husband, Muhammad Abu Shaar. As Israel and Egypt are not allowing journalists to enter Gaza, I have not met her. I haven’t been able to find out her name, which was not posted alongside those of her dead husband and children.

In the video, it is as if she hopes, somehow, that the power of her grief will bring him back.

“I swear, we promised to die together. You died and left me. What are we supposed to do, God? Muhammad, get up! For God’s sake my beloved, I swear to God, I love you. For God’s sake get up. Our children Nour and Aboud are here with you. Get up.”

The two children were with their father because all three of them had just been killed by Israel. An air strike destroyed the house they were hoping would shelter them in Rafah.

Yonatan Zeigen

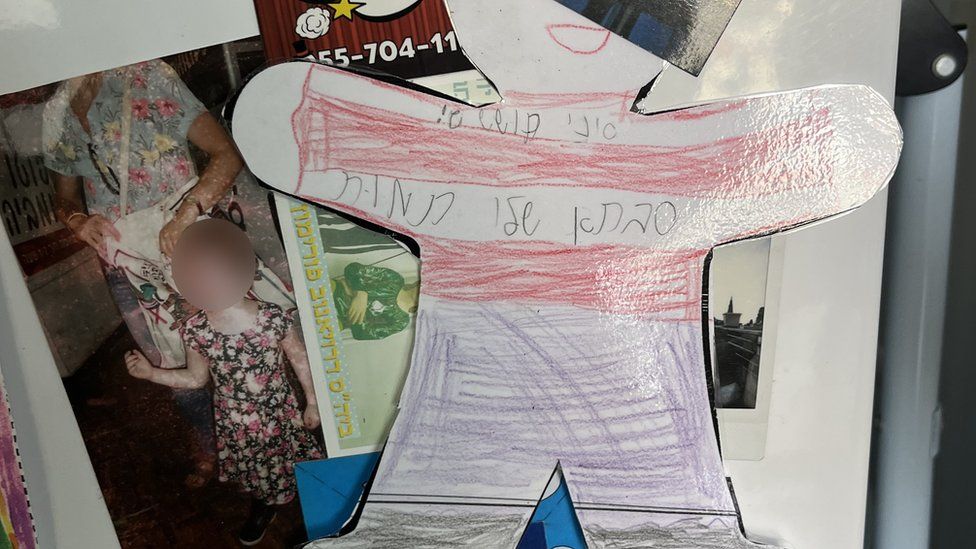

I visited Yonatan Zeigen at his flat in Tel Aviv. It was a comfortable home, full of his children’s toys. Among the family photos I recognised his mother, Vivian Silver, who was one of Israel’s leading campaigners for peace with the Palestinians. Vivian was in the family home in kibbutz Be’eri, on the border with Gaza, when Hamas attacked on 7 October.

The first time I met Yonatan, in the days after their kibbutz was attacked, he was hoping his mother had been taken into Gaza as a hostage.

When he heard the air raid sirens in Tel Aviv, he rang Vivian. They switched to WhatsApp as they heard gunfire and explosions in the kibbutz, hoping that if she made no noise, Hamas would bypass the house.

He read out the texts they exchanged, first some black humour and suddenly serious and full of love as she realised a massacre was happening.

“She wrote me, they’re inside the house, it’s time to stop joking and say goodbye,” he tells me.

“And I wrote back that ‘I love you, Mum. I have no words, I’m with you’. Then she writes, ‘I feel you’. And then that was it, that’s the last message.”

The next day, I visited her house in the kibbutz and saw it was burnt out. It took weeks for investigators to find Vivian Silver’s remains in the ash left behind in the safe room. Yonatan has given up his career as a social worker to campaign for peace.

“They came into my country and killed my mother because we didn’t have peace. So, to me, this just proves the point that we need it,” he says.

“It could go either way. Catastrophes like this create changes in societies in the world. And I believe that it can lead to a better future.”

Issa Amro

Issa Amro is a Palestinian activist in Hebron in the West Bank. The city is holy to Muslims and Jews, who revere it as the burial place of the prophet Abraham. It has been a flashpoint for decades.

Issa is well known in Hebron and considered a troublemaker by Israeli soldiers who have enforced a curfew on Palestinians who live near the Jewish settlement in the heart of the city. He told me he was detained and beaten after the 7 October attacks.

Like Yonatan Zeigen in Tel Aviv, Issa Amro believes that the war could produce a chance for Israelis and Palestinians to lead better and safer lives.

“I think it’s two opportunities. Either we choose to make it deeper and worse, or we make it as an opportunity to solve the conflict and to solve the occupation, to solve the apartheid and make living together possible because the security solution failed… only peace is the solution.”

The prospects for peace

It might seem a long way off now, and many more people are going to be killed before it happens, but like every war this one will stop.

All the wars in and around Gaza since Hamas seized control there in 2007 have ended the same way, with a ceasefire deal. The ceasefires all came with a fatal flaw that guaranteed the next war between Israel and Hamas. That was because no attempt was made to end a century of conflict between Palestinians and Israelis.

The killing and destruction in this war are of such a different order that no one can pretend there is any kind of normality to restore. This time it must be different. That much is accepted by Palestinians and Israelis and the outside powers that matter the most.

The problem is agreeing which future to try to create. The Israeli government is heading for a diplomatic row with the United States, its most important ally, about what happens after the ceasefire.

President Joe Biden is exasperated by what he called Israel’s “indiscriminate bombing” of Gaza. Even so, he continues to back Israel, as he has since the start of the war, by deploying aircraft carriers, sending planeloads of weapons and vetoing ceasefire resolutions at the UN Security Council.

In return, Joe Biden wants Israel to agree that the only way forward is revive talks to establish an independent Palestinian state. That was the objective of the Oslo peace process, which failed after years of negotiations.

Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has not said much about how Gaza would be governed if and when he declares victory over Hamas. But he has rejected Joe Biden’s plan.

One constant in Netanyahu’s long political career has been opposition to the independent Palestinian state that Oslo tried and failed to produce.

Total victory and the unconditional surrender of anyone left alive in Hamas remain Israel’s objectives. Annihilating Hamas, Mr Netanyahu believes, is the only way to rescue the hostages.

A few hours before Mr Biden said Israel’s bombing was indiscriminate, Mr Netanyahu made his own speech.

“I will not allow Israel to repeat the mistake of Oslo,” he said. “After the great sacrifice of our civilians and our soldiers, I will not allow the entry into Gaza of those who educate for terrorism, support terrorism and finance terrorism. Gaza will be neither Hamastan nor Fatahstan.”

Fatahstan is a derogatory reference to the Palestinian Authority, the rival to Hamas, which recognises Israel and co-operates with it on security.

Israeli domestic politics feed into Mr Netanyahu’s calculations. Opinion polls indicate that many Israelis blame him for the intelligence and security failures that allowed Hamas to break into Israel with such force. By doubling down on his opposition to Palestinian self-determination, Mr Netanyahu is trying to regain the trust of the right-wing Jewish nationalists who support his government.

Yonatan Zeigen, the son of the slain peace campaigner Vivian Silver, says his mother would have been heartbroken to see the war, believing that wars cause more wars.

“I think she would have said ‘not in my name’… a war, if we’re not too naïve, should be a means, right? But it feels like this war is a cause in itself, of revenge.”

Yonatan senses a new opportunity, to put peace back on Israel’s political agenda.

Peace campaigners were prominent in Israel until they were discredited as an armed Palestinian uprising erupted after the Oslo process collapsed in 2000. The idea of peace with the Palestinians vanished from mainstream Israeli politics. Now, Yonatan hopes, it is inching its way back.

“Absolutely. You couldn’t even say the word. And now people are talking about it.”

Issa Amro, the Palestinian activist in Hebron, told me life there is much harder for Palestinians since 7 October.

“It got much worse. Ten times worse. More restrictions. More violence. More intimidation. People don’t feel safe at all. People don’t have enough food to eat. People don’t get any access to a social life. No schools, no kindergartens, no work. It’s a collective punishment inside an area which is very restricted.”

Issa got into a verbal spat with a group of Israeli soldiers while we were walking with him through the centre of Hebron. One of them, in combat gear, with an assault rifle and large pistol in a holster, wearing a black mask that only exposed his eyes, listened closely as Issa told me that peace was the only way ahead as there was no military solution to the conflict. The soldier wouldn’t give his name when he butted into the conversation.